The Story of a Mother’s Hope Fulfilled

By: Jeff Joiner | August 9, 2023

When Yolanda Medina MPA’12 began interviewing her mother during frequent visits to her native Puerto Rico, she had no idea that she would learn about a devastating childhood framed by desperate poverty and frequent abuse. But over time, her mother’s story became one of perseverance and hope, and Medina realized she had to tell the world about Josephina Sanchez.

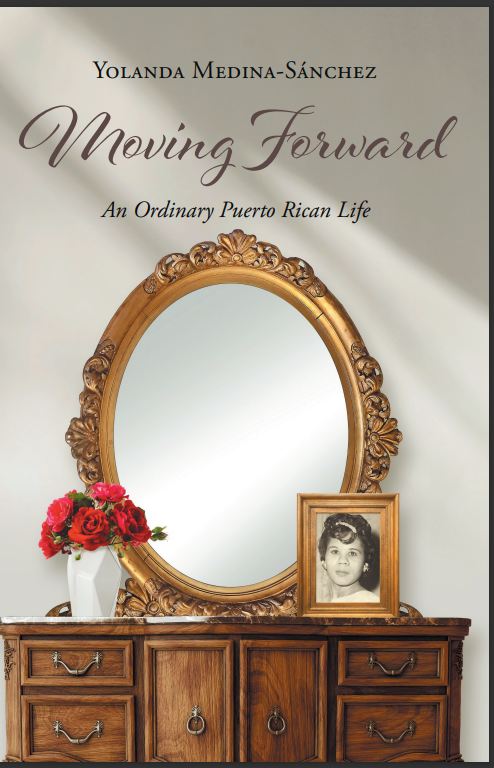

“This is my mother’s story,” Medina said, holding up a photo of the memoir, “Pa’lante: La vida Ordinaria de una Puertorriqueña” or “Moving Forward: An Ordinary Puerto Rican Life.” The memoir, which is available in Spanish and English, was published in January after six years of writing, editing and translation, and many more years collecting Josephina’s stories.

What began as a way for Medina to learn more about her mother’s life became a project honoring the survival of a horrific childhood and unhappy marriage and the eventual evolution into the foundation of a family’s strength.

“I think she was a remarkable woman,” Medina said. “And I wanted to make sure everyone in my family knew her life.”

In 1991, Medina, who earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the University of Puerto Rico before attending UTD, moved from Puerto Rico to Dallas for a job as a librarian. Close to her mother and six siblings, Medina often returned home to visit and began asking her mother about her life and recording stories in a composition notebook. The first thing Medina asked about was early memories of her own mother. The answer she received shocked her and from that moment changed the rest of her life.

“What she tells me is a horrible story,” Medina said. “When she’s 8 years old her mother catches her eating dirt. To punish her she decides to tie her up and hang her upside down from a tree and set her hair on fire. This is what she’s telling me, and I start writing.”

Fortunately, a neighbor heard the girl’s screams and saved her from more serious injury. But the story is just one of many from a tragic childhood that Medina and her siblings had never heard.

“I believe that maybe she was ashamed. She didn’t speak openly about her life until I started asking her questions,” Medina said. “Once she opened herself up to me, the stories gushed out.”

From 1992 until her mother’s death in 2014, Medina wrote down story after story, documenting abuse and the family’s life in poverty. At age 9, Josephina’s mother left her with another Puerto Rican family to work as a live-in maid. Though the family treated her well, she wasn’t allowed to attend school and only completed third grade.

“She does everything — the cooking and the cleaning for this family – and at 9 years of age,” Medina said.

At age 12, Josephina returned to her mother, but the abuse resumed, and she moved in with another family as their maid. She married at 16 and soon after moved to New York City with her husband to work in the city’s textile manufacturing sweatshops. It was there that Medina, the oldest of seven children, was born in 1955 when her mother was 18. When Medina was 12, the family moved back to Puerto Rico after facing the same poverty in New York as back home. Despite attempts to improve their situation, Josephina still faced an unhappy life with a mostly absent, womanizing husband.

Medina recorded not only stories of abuse, but also recollections of her mother’s resilience and how that upbringing made her a strong family matriarch. Much of her mother’s determination resulted in raising strong children like Medina, who was so determined to tell her mother’s story that she took five creative writing classes at Collin College to learn how to write and publish a memoir.

Although she was born in New York City, Medina made the difficult transition to a childhood in her family’s native Puerto Rico, attending public schools and then the University of Puerto Rico, where she earned a bachelor’s degree and a master’s in library science before working as a librarian on the island. In 1991, Medina and her two young daughters moved to Dallas for the promise of a job. She worked briefly as a librarian for the Dallas Public Library and then for several years with the Richardson Public Library until retiring.

A manager of outreach programs in Richardson, Medina taught classes to library patrons including English as a second language and English citizenship. With an interest in literacy throughout her career, Medina enrolled in UTD’s Master of Public Affairs program in the School of Economic, Political and Policy Sciences in 2006. The degree helped her start a literacy nonprofit she founded after graduating, the Central Latino de Educación para Adultos Dallas Norte, or the Latin Center for Adult Education of North Dallas, which she still directs today. Through the center, Medina and her volunteers teach basic literacy to Hispanic immigrants who come to North Texas to live and work. To date, Medina has taught basic literacy for nearly 17 years, including to more than 300 adult learners who have graduated from elementary, middle school and GED programs through the library and her nonprofit.

Medina knows firsthand how much literacy builds a person’s self-esteem. When her mother was in her 40s, she enrolled in basic Spanish literacy classes for custodial employees of the University of Puerto Rico where she worked. With only a third-grade education, four years of classes brought Josephina up to a ninth grade reading and writing level.

“She was so proud of going back to school and learning all these things,” Medina said.

On trips to Puerto Rico this year, Medina has read from her memoir at bookstores and libraries, including at one reading attended by her siblings. Her mother’s story has struck a chord with many whose own mothers and grandmothers experienced similar upbringings marked by poverty and lack of opportunity. According to Medina, the book’s title “Moving Forward: An Ordinary Puerto Rican Life” is a reference to those like her mother who believe their lives are not important.

“She asked me once why I wanted to write about her life,” Medina said. “‘I haven’t done anything important,’ she said. She thought that because she wasn’t a doctor or an engineer or something like that that she wasn’t important. She thought she was just an ordinary person. But she raised a family and despite a horrible childhood learned to be happy. And her children share that happiness.”

Learn more about the book at www.yolandamedinabooks.com.